The joint report Eat Fat, Cut The Carbs and Avoid Snacking To Reverse Obesity and Type 2 Diabetes published by selected members of the National Obesity Forum (NOF) and Public Health Collaboration (PHC) has caused quite a stir. A number of the NOF board have now resigned with some distancing themselves entirely from the report and the The Royal Society for Public Health went as far as labelling it a “muddled manifesto of sweeping statements, generalisations and speculation”. Ouch.

I thought it would be worth doing a quick fact check of some of the claims made in this report. To avoid the inevitable strawman criticism which will come my way, I am not asserting that the overall message of the report is right or wrong, nor am I advocating for a particular diet in this post.

What I am saying however is that if you wish to make a coherent argument it should be i) internally consistent and ii) supported by citations which say what you claim they say.

Comments are enabled so let me know if I have made any errors myself, or if you spot anything I have missed. I’ll be happy to correct.

Section 1. Eating Fat Does Not Make You Fat

“Evidence from multiple randomised controlled trials have revealed that a higher fat, lower carbohydrate diet is superior to a low-fat diet for weight loss and cardiovascular disease risk reduction [8, 9]”

The first reference [8] is a meta-analysis by Sackner-Bernstein et al. The cited paper does indeed conclude that Low-Carb diets are superior for weight loss and reducing markers of CVD risk. However the nuance that their superiority is “numerically modest” is excluded from the NOF/PHC report:

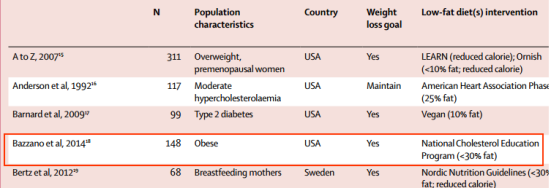

The second reference [9] also supports that claim. A minor gripe here though, if we are making the case about multiple trials showing benefit why is this particular individual Randomised Controlled Trial (RCT) Bazzanno et al worthy of note when there are meta-analyses available?

“An exhaustive analysis of 53 randomised controlled trials involving 68,128 participants conducted by the Harvard School of Public Health concluded“ when compared with dietary interventions of similar intensity, evidence from randomised controlled trials does not support low fat diets over other dietary interventions for long term weight loss. In weight loss trials, higher fat weight loss interventions led to significantly greater weight loss than low fat interventions.”

No citation is provided for this claim. Sloppy, but not a big problem as it’s a recent and relatively easy to find paper with the information provided: “Effect of low-fat diet interventions versus other diet interventions on long-term weight change in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis” by Tobias et al. The quote cited does indeed appear in this meta-analysis.

Again, a minor gripe but the Bazzano et el paper cited by the NOF/PHC separately as reference [9] is one of the papers considered within this meta-analysis, so there is a minor element of double counting of evidence here. Its hardly significant, but it is indicative that a systematic approach has not been taken by NOF/PHC in term of identifying and presenting the body of evidence.

One other point which we will come back to is that this meta-analysis considers not just low-carb, high fat and low-fat dietary comparisons – where data is available – but also separates the trials into studies aimed at weight loss (with and without weight loss goals) and weight maintenance.

Things now begin to go downhill as they focus on one particular trial:

“Furthermore the Women’s Health Initiative was the largest randomised controlled diet trial ever performed”.

Its not clear why the NOF/PHC feel that this RCT trial in particular needs to be discussed further, especially when it was another RCT which was included within the previously cited meta-analysis by Tobias et al.

48,835 post-menopausal women were randomised to either their usual diet or a low-fat, calorie reduced diet with increased exercise with the hypothesis that this would reduce cardiovascular disease.

Inaccurate in one important aspect. According to the citation it was a dietary modification trial in which participants were counselled to change the composition of their diet but not to reduce energy intake (i.e. there were no weight loss goals):

“The intervention achieved an 8.2% energy decrease in total fat intake and a 2.9% energy decrease in saturated fat intake, but did not reduce risk of CHD or stroke.[10]”

Correct.

While not specifically a weight loss trial, nevertheless, the reduction in dietary fat and total daily calories (361 calories/day reduction) also failed to produce any significant weight loss over the duration of the study.

It was not a weight loss trial, it was a weight maintenance trial.

The reduction in daily calories does not appear in the cited paper anywhere. There is however a separate paper from the Women’s Health Initiative trial titled “Low-Fat Dietary Pattern and Weight Change Over 7 Years” so it looks like a citation error. The reduction in calories is taken from Table 2 of this paper and it represents the final nutrient intake (baseline minus follow-up) estimated by Food Frequency Questionnaire (FFQ):

It is extremely misleading to take a figure from the follow-up FFQ and present this as if this was a calorie deficit which was achieved and maintained for the duration of the trial (“361 calories/day reduction”). It gives a false impression that large and sustained energy deficit was achieved, yet significant weight loss was not. We also don’t know, of course if participants were at energy balance at baseline.

It is even more misleading when you consider that data obtained from FFQs are well known to have weaknesses and that the authors of the paper explicitly highlights this issue to prevent misinterpretation:

This isn’t the first time the PHCUK have misused self reported data without acknowledging the uncertainty in the measurement – even when the dangers of this are explicitly stated by their source.

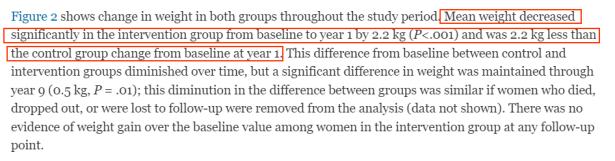

As for the claim that Women Health Initiative trial failed to “produce any significant weight loss over the duration of the study” I’ll leave you to decide if that claim is true:

(But the answer is: no, it’s entirely untrue).

As an aside, the dietary pattern and weight change paper is well worth reading in full because it also includes statements like the one below which are, ahem…let’s say inconvenient to the pro-fat argument that the NOF/PHC are trying to craft:

“This rejected the notion that the low-fat diet is either beneficial for cardiovascular disease or weight loss.”

I think the NOF/PHC have a problem here with the consistency of their argument. It’s rather strange to put forward the argument that low fat diets are “not beneficial for cardiovascular disease or weight loss” based solely on one (albeit large) RCT when they have already cited other evidence which tends to refutes that claim.

Remember the Sackner-Bernstein et al meta-analysis cited at the start of this section of the NOF/PHC report which they used to argue for the superiority of low-carb diets over low-fat diets? It concludes:

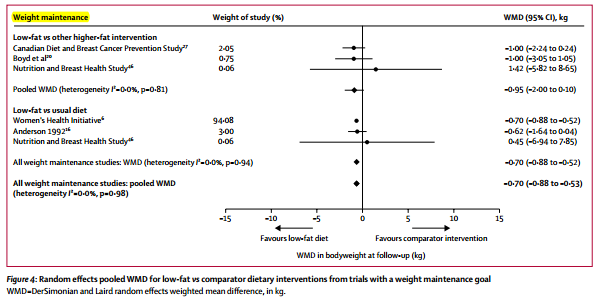

What about the Tobias et al meta-analysis – which includes the WHI study – and looks at weight loss and weight maintenance? It shows that the low fat diet is superior to the standard diet for weight loss (with and without goals) and for weight maintenance, and that they were broadly not significantly different from higher fat diets unless they also restrict carbohydrate.

“We recommend that guidelines for weight loss for the UK should include an ad libitum low refined carbohydrate and a high healthy high fat diet (i.e non-processed foods or “real” foods) as an acceptable, effective and safe approach for preventing weight gain and aiding weight loss.”

It is unclear which data is being used to support the use of low refined carbohydrate diets for long term weight maintenance. According to the Tobias et al meta-analysis cited by NOF/PHC “no long-term non-weight loss or weight maintenance trials compared low-fat with low-carbohydrate dietary interventions”:

Section 9. Snacking will make you fat (Grandma was right!)

There have been two major changes in our dietary habits since the 1970s, prior to the onset of the obesity epidemic. The change to a high carbohydrate, low fat diet has been well documented and has played an important role in causing obesity.

Assertion and questionable language. The change to a high carbohydrate diet is causing, or is associated with increasing obesity? (Answer: the latter, if you care about not committing the post ergo propter hoc fallacy).

The other change, the increase in meal frequency plays an equal if not larger role and has been largely ignored. In the 1970s, the average number of eating opportunities was three – breakfast, lunch and dinner. Fast-forward to 2005 and that number has almost doubled. [40]

If I’ve understood this properly the position taken by the NOF/PHCuk is that obesity in the UK has been driven not by increasing calorie intake, but by an increase in insulin secretion caused by frequent high carbohydrate meals. The citation leads to this cross sectional study. The cited study does indeed confirm that frequency of eating opportunities has increased since the 1970’s, but in the USA.

If we accept that the UK and USA are broadly similar we are still left with a couple of issues before we accept the above argument: i) cross-sectional studies cannot show causation ii) the citation makes the case that the increase in eating opportunity in the USA also correlates with an increase in overall energy intake (i.e. not one of the two major changes to diet identified by the NOF/PHC):

To further developing the idea that meal frequency is one of the major factors in increasing obesity the following claim is made:

“Eating continuously from the moment we arise to the moment we go to sleep does not allow our body to digest and use some of the foods that we eat. The entire day becomes an opportunity to store food energy without a chance to burn it. Eating six times a day does not result in weight loss (41), but tends to increase overall consumption of food.”

The third sentence is interesting and the citation for this is “Increased meal frequency does not promote greater weight loss in subjects who were prescribed an 8-week equi-energetic energy-restricted diet” by Cameron et al. This is a small RCT (n=16) looking at the hypothesis that a high meal frequency (MF) might lead to a greater weight loss than that obtained with a low MF under conditions of similar energy restriction.

The absolute claim that “eating six meals a day does not result in weight loss” is directly contradicted by the citation. Over eight weeks participants in the high-MF group (3 meals/day and 3 snacks/day) did in fact lose weight: Weight loss is entirely unsurprising, since despite having six meals per day the protocols were designed to achieve an energy deficit in both low-MF and high-MF groups:

Weight loss is entirely unsurprising, since despite having six meals per day the protocols were designed to achieve an energy deficit in both low-MF and high-MF groups:

The claim that six meals per day “tends to increase overall consumption of food” might be true, but due to the design of this study, which involved the participants actively trying to lose weight by adhering to a prescribed calorie deficit, it cannot support that claim.

Authorship and Peer Review

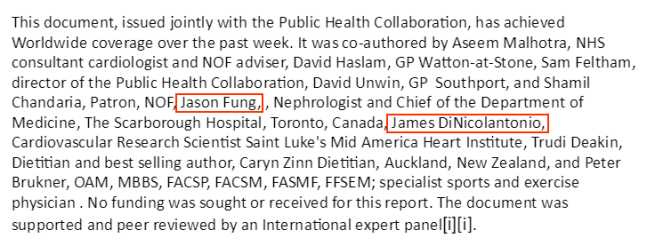

While initially the document was issued without any acknowledgement of authorship we now know via a statement on the NOF website that a large number of individuals were co-authors. Some of these have competing interests (e.g. David Haslam sits on the scientific advisory board for Atkins Nutritional, Sam Feltham has a diet book for sale based on the principles in this report) and for transparency these really should have been identified in a statement of competing interests.

It seems unusual that there was also an “expert panel” who “supported” the paper as well as “peer reviewing” it before publication? Where is the line drawn between support and co-authorship? – this isn’t at all clear.

Some of the people are listed as “co-author” and “peer reviewer” (is that even possible?) while others are clearly not experts – “Film maker and health activist”, “Best-selling author and health activist”.

I think it would have been better to simply say the paper has not been externally peer reviewed and leave it at that.

Conclusion

Having reviewed a couple of sections of the report in detail and skimmed the remainder the bias within this document is plain to see and there are serious issues about the way this report was authored and checked.

There is little evidence that a systematic approach has been taken to identify and appraise relevant evidence to inform their claims and it relies quite heavily upon simple unreferenced assertion to make the case for higher fat diets.

The benefits of high fat and low-carb diets are presented in a way which would lead the casual reader to expect major benefits and superiority over alternatives, when in fact this is often shown to be marginal, or there is simply insufficient data to justify the conclusions drawn by NOF/PHC (e.g. low-carb diets for weight maintenance).

It’s apparent that there is a sloppy approach to citations, and some of the claims made are just plain wrong. It’s baffling that this large cohort of co-authors and an equally large cohort of “peer reviewers” didn’t check the claims they were making sufficiently, or possess sufficient understanding/expertise or impartiality to interpret the data in a more even handed manner.

The NOF/PHC need to acknowledge and correct the obvious errors within this report.